“Avoid the North American part because there is only television, you hear?”

Cassia Hosni

The inclusion of moving images into the exhibitions of the São Paulo Biennial in the early 1970s can be seen as a setting of technical, aesthetic, and geopolitical conflict. Such conflicts proliferated due to the very model adopted by the event (and abandoned only in 2006, in its 27th edition), which was based on national representations wherein the invited countries pay for the transport of works and equipment—and therefore have the final word on what will be displayed. It is not by chance that this regime attributed greatest importance to financial aspects, allowing the great economic powers to have greater prominence. Far from detailing the specifics of each edition, what is proposed here is a reflection on some issues in the ways in which video works were exposed, viewed, and received by critics and the public in a period that was sensitive towards the audiovisual.

1. Technical

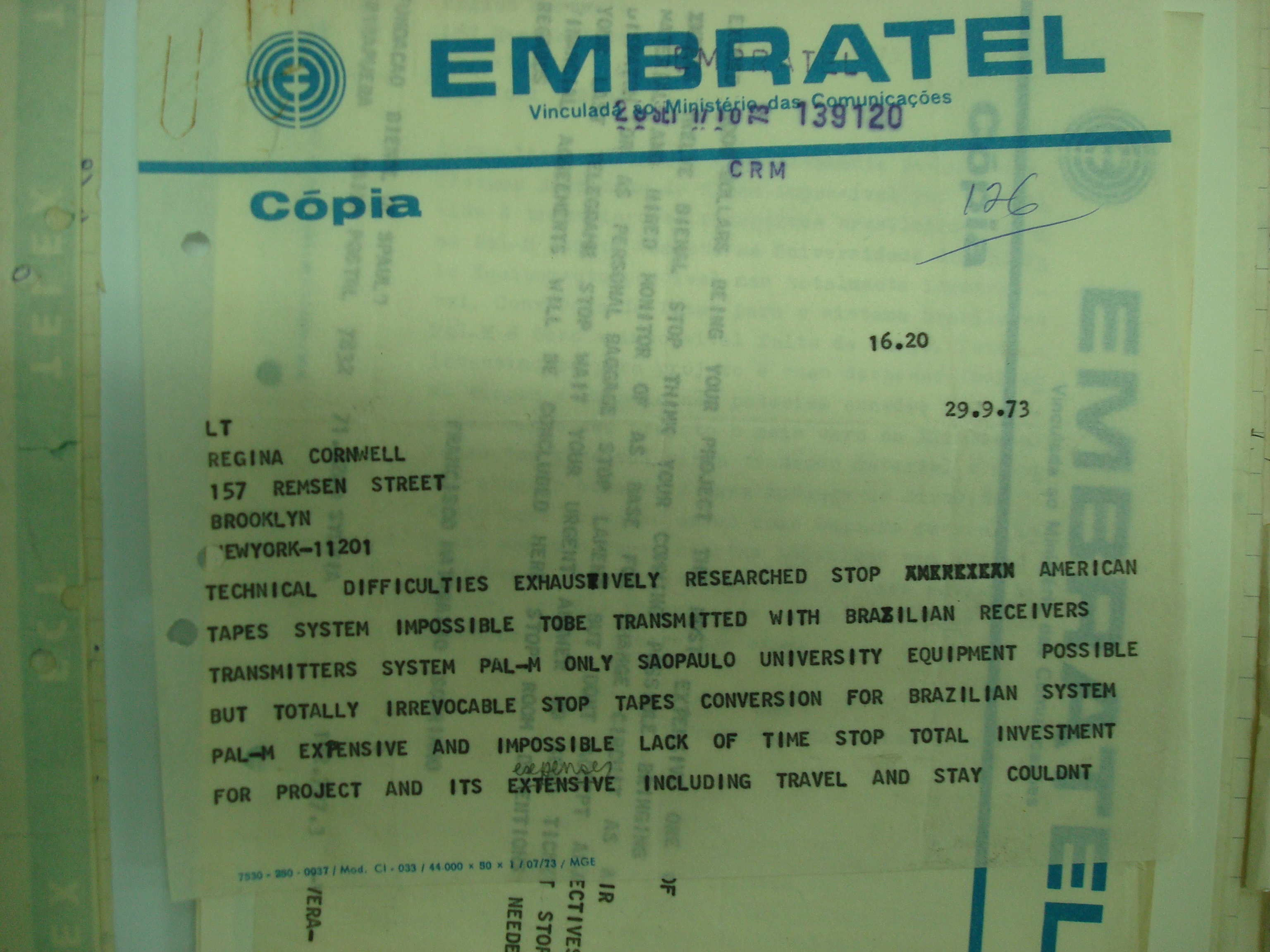

It was in 1957 that the Pavilion of Industries, today the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, became the exhibition space for the São Paulo Biennial. The sinuous building built by Oscar Niemeyer was originally intended to house agricultural machinery and not to display works of art. Thus, it was natural that in the 1970s the space presented problems for the first attempts to exhibit works with moving images. The 12th São Paulo Biennial (1973), for example, featured the Art and Communication section—whose purpose was to be a laboratory for reflecting on technology, art, and society. In this edition, in the face of numerous bureaucratic problems, what actually was presented was a stunted version of what was originally envisioned. A series of technical problems, such as the lack of necessary equipment and the conflict between the PAL and NTSC systems, affected the US and Swiss delegations, posing obstacles to the exhibition of works in the pavilion. However, as recently analyzed by Paulina Pardo Gavíria, videotapes from the United States were shown in the edition with the help of MoMA equipment. In the 13th edition, electrical problems abounded: from voltage drops in electrical installations—as happened with Peter Campus’ video installation—to problems installing outlets.

2. Aesthetic

In Brazil, from the 1970s onwards, a group of visual artists carried out investigations with video, constituting what became known as the “pioneer generation of video art.” Despite all the difficulty in accessing equipment, initiatives by groups of artists from São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, as well as institutions such as MAC-USP and MAM/RJ, were fundamental at a time marked by the curtailment of individual freedoms by the civil-military dictatorship.

In addition to these issues, established critics viewed this new production with reservation as a medium that was not recognized in the local artistic circuit. Walter Zanini reminds us that the criticism made of video art was that it would be an “imported” or “colonized” art and mentions that “the critic, almost always with a conventional attitude, generally received this investigation with disinformation or coldness, assimilating little or nothing of it or already conferring upon it the epitaph of bedazzling.” Frederico Morais also notes that in this period the public reaction was generally negative: “They consider it monotonous due to the exhaustive repetition of the same image, to its static character (against the dynamism of commercial TV), due, in short, to the discomfort that is, in fact, more psychological than real, given the relaxed or comfortable way we watch TV at home.”

Nor did the public seem favorable to the use of the media: “Avoid the North American part because there is only television, you hear?” was the comment of one of the spectators of the 13th São Paulo Biennial (1975), heard by a reporter and recorded in the newspaper. In this edition, the United States delegation exhibited the Video Art USA exhibition, a selection made by the curator/commissioner Jack Boulton, which featured video installations such as TV Garden by Nam June Paik, the closed-circuit projection Sev by Peter Campus, and a selection of videotapes that highlighted the process of diffusion of North American video art. The selection included Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Lynda Benglis, Bill Viola, Steina and Woody Vasulka, Joan Jonas, Andy Warhol, among others—a strong team, made up of artists who are now included in the history of contemporary art, whether because of conceptual bias or because of innovation in the field of video technology. It was already notable at the time that the American delegation presented a video art curatorship focused on export.

At that moment, the best way to present videotapes was still being explored. For the 1975 show, the American delegation presented two rooms: one housed the exhibition of all the works, totaling 8 hours; the other featured short excerpts from the works, assembled into an hour-long videotape. Despite the double presentation—in the room with the impossible duration and in the room with the “greatest hits”—the international selection jury of the São Paulo Biennal did not view the works, which was considered an affront by the United States delegation. In a statement at the time, commissioner Boulton said that “video art is like a symphony, which has to be heard until the end.” Even so, to facilitate the reception of all the work, a special room had been set up where, in a large video, a summary of all the works exhibited could be seen. “A one-hour summary, which the jury did not want to watch completely.”

3. Geopolitical

The fact that the international award jury, composed of Werner Schmalenbach (Germany), Rafael Squirru (Argentina), Jean Dominique Rey (France), Fernando Gamboa (Mexico), and Paulo Mendes de Almeida (Brazil), did not view the works of the delegation of American artists at the 13th São Paulo Biennial caused controversy. In view of the delegation's complaints, members of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA), the Brazilian Association of Art Critics (ABCA), and the São Paulo Association of Art Critics (APCA), in addition to numerous artists, sympathized with it through a petition delivered to the Biennial Foundation. In response, an explanatory note was issued in the edition's catalog, in which the jury regretted not having viewed the works due to technical problems and lack of time, but they recognized the country's contribution as having extraordinary value. This small conflict compels a question regarding the forms of reception of video art at the time of its emergence in Brazil in the 1970s: could the solidarity shown in relation to the North American delegation also present itself in the face of our own video production?

A point to remember is that the original Video Art exhibition—held between January and February 1975 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Pennsylvania by Suzanne Delehanty and the basis for Jack Boulton’s assembling the selection for Video Art USA, presented later in the same year at the 13th Biennial—had the participation of Brazilian artists, such as Sonia Andrade, Fernando Cocchiarale, Anna Bella Geiger, and Ivens Machado. In the North American section of the Biennial catalog, there is no mention of Brazilian artists or those of other nationalities who participated in the original exhibition.

This fact highlights how, at that time, the Biennial itself, through the clash between national versus international artists, was not concerned with disseminating the experimental productions of local artists. The production created in Brazil was shown internationally at the show that gave rise to the North American representation; however, when part of this exhibition comes to the country, the dialogue is suppressed, as if there were two distinct entities without communication: on the one hand, Brazil, the place of reception, and, on the other, the United States, the country of creation and exporter of contemporary trends.

When looking with a magnifying glass at this point in the history of the São Paulo Biennial, we can discover indicative moments that still resonate with how national artistic production itself is seen—indicative of our formation, of the search for dialogue, and also of international validation, in detriment of the recognition and clear perception of what is manifested locally. In this sense, it is worth questioning the place of video art as a showcase for the creation of North American culture in exhibitions such as the 13th São Paulo Biennial—in which the plural and internationalist Video Art show became Video Art USA.

Assistance from national institutions and financial support are vital for the circulation and reception of artists and their works: it is worth remembering, for example, that the famous video Global Groove by Nam June Paik was the result of a grant that the South Korean obtained from the Rockefeller Foundation in New York, and that when he applied, the original proposal had the suggestive title “to destroy national television.” All this effort in the diffusion of the new medium between the 1960s and 1970s appears today recorded in western books of art history, in a way that makes it valid to question why the Brazilian “pioneer generation” is not inserted in the global circuit with the same degree of relevance as its counterparts in the northern hemisphere.

The reception of Brazilian video art in the 1970s presents tensions that, with regard to the São Paulo Biennial, will only be considered and worked on in the early 1980s—when national video art, based on the experiments carried out by Walter Zanini at MAC-USP, entered the Biennial Pavilion with due attention and interest.

Assistance from national institutions and financial support are vital for the circulation and reception of artists and their works: it is worth remembering, for example, that the famous video Global Groove by Nam June Paik was the result of a grant that the South Korean obtained from the Rockefeller Foundation in New York, and that when he applied, the original proposal had the suggestive title “to destroy national television.” All this effort in the diffusion of the new medium between the 1960s and 1970s appears today recorded in western books of art history, in a way that makes it valid to question why the Brazilian “pioneer generation” is not inserted in the global circuit with the same degree of relevance as its counterparts in the northern hemisphere.

The reception of Brazilian video art in the 1970s presents tensions that, with regard to the São Paulo Biennial, will only be considered and worked on in the early 1980s—when national video art, based on the experiments carried out by Walter Zanini at MAC-USP, entered the Biennial Pavilion with due attention and interest.

Referências bibliográficas

A BIENAL dos vencedores e dos esquecidos. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, Ilustrada, 17 out. 1975.

FUNDAÇÃO BIENAL DE SÃO PAULO. 13ª Bienal de São Paulo. São Paulo: Biennial Foundation, 1975. Exhibition catalog.

GAVÍRIA, Paulina Pardo. “Lent for Exhibition Only: TV Screens at the São Paulo Biennial”, Arts of the Screen in Latin America, 1968–1990, College Art Association (CAA)

HOSNI, Cássia Takahashi. Zona Cinza e a espacialização da imagem em movimento: Instalações audiovisuais na Bienal de São Paulo e na Biennale di Venezia. 2021. Thesis (Doctorate in Architecture and Urbanism)—College of Architecture and Urbanism, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 2021.

HOSNI, Cássia Takahashi. Zona Cinza e a espacialização da imagem em movimento: Instalações audiovisuais na Bienal de São Paulo e na Biennale di Venezia. 2021. Thesis (Doctorate in Architecture and Urbanism)—College of Architecture and Urbanism, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 2021.

MORAES, Frederico. Vídeo-Arte: Revolução Cultural ou um título a mais no currículo dos artistas? [1976]. In: PECCININI, Daisy (Coord). Arte Novos Meios / Multimeios: Brasil 70/80. São Paulo: Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation, 2010. pp. 73 ̶ 75.

RIBEIRO, Leo Gilson. XIII feira internacional de vaidades nacionais. O Estado de S. Paulo, São Paulo, Oct. 28, 1975.

ZANINI, Walter. Vídeo-arte: uma poética aberta [1978]. In: PECCININI, Daisy (Coord). Arte Novos Meios / Multimeios: Brasil 70/80. São Paulo: Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation, 2010. pp. 87 ̶ 92.

RIBEIRO, Leo Gilson. XIII feira internacional de vaidades nacionais. O Estado de S. Paulo, São Paulo, Oct. 28, 1975.

ZANINI, Walter. Vídeo-arte: uma poética aberta [1978]. In: PECCININI, Daisy (Coord). Arte Novos Meios / Multimeios: Brasil 70/80. São Paulo: Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation, 2010. pp. 87 ̶ 92.