Creation and care in mixing vibrating/material bodies

jialu pombo

I dedicate this text to my aunt Fátima Pombo.

This text is a small expression of the affections that mark the event of my encounter with Lygia Clark. But make no mistake, since I was born in the 1980s, this meeting was not of flesh and blood, or face-to-face, as we would say in our massively online parlance. Nor was/is it merely virtual – it does not exist merely as potency, and it has a strong effect on reality. From the 1990s, when the first episode of this meeting probably took place, until this moment as I write these words, I have had time to elaborate and expose something of what is happening here, something of the mixture that happens between our “vibrating bodies.”1 And to this mixture are also integrated other2 agents that cross our paths. In this text, I relate creation and care (bringing my own expressions to what Suely Rolnik called art and clinic) with some things that Lygia carried out/proposed, and I do this based on my trajectory as someone who creates and cares (someone who is created and cared for).

How many beings am I to always seek the realities of contradictions from the other being that inhabits me? How many joys and pains does my body have, as it opens like a gigantic cauliflower offered to the other being that is secretly inside me? Inside my belly lives a bird, inside my chest, a lion. It wanders to and fro incessantly. The bird quacks, kicks and is sacrificed. The egg continues to envelop it, like a shroud, but it is already the beginning of the other bird that is born immediately after death. There isn't even a break. It's the feast of life and death intertwined. (CLARK, 1967. In LINS, 1996. In ROLNIK, 2015. p. 104)

1 Expression by Suely Rolnik, which the author uses in several texts, in some writings with a hyphen – “vibrating-body,” as it appears here later. My encounter with this expression took place while reading the book Sentimental Cartography – Contemporary Transformations of Desire, in which we see that the vibrating body is “the one that reaches the invisible. A body sensitive to the effects of encounters of bodies and their reactions: attraction and repulsion, affections, simulation in matters of expression” (1989. p. 26). I create a unique relationship with this expression, articulating it with what I call the material body, in the sense of the material layers of existence, the physicality of the flesh. The intertwining and integrality of vibrating and material is already expressed in the title with the term “vibrating/material bodies,” which is explored throughout this text.

2 Translator’s note: This footnote references the author’s decision to use the term “outroa” instead of “outro” or “outra.” Since a gendered distinction does not exist for the English word “other,” the usage of “outroa” in the original text cannot be expressed in the translation]. An articulation I use to avoid submitting to the binary division of gender in words, a formulation that I believe is possible to use in spoken language and not just in writing. Thus, the proposed reading is that in words with the sequence of letters that, in Portuguese, would indicate the masculine or feminine connotation (example: o or a) the sonority is continuous and not interrupted, that is, when faced with the word “outroa,” read outroa and not outro/outra. The mixed use of letters proposes a de-characterization of gendered readings.

2 Translator’s note: This footnote references the author’s decision to use the term “outroa” instead of “outro” or “outra.” Since a gendered distinction does not exist for the English word “other,” the usage of “outroa” in the original text cannot be expressed in the translation]. An articulation I use to avoid submitting to the binary division of gender in words, a formulation that I believe is possible to use in spoken language and not just in writing. Thus, the proposed reading is that in words with the sequence of letters that, in Portuguese, would indicate the masculine or feminine connotation (example: o or a) the sonority is continuous and not interrupted, that is, when faced with the word “outroa,” read outroa and not outro/outra. The mixed use of letters proposes a de-characterization of gendered readings.

The intertwining between life and death that Lygia talks about is what I call the expression of vulnerability-force: there is a force present in an embryo that carries potential information of life, and for such a life to come into existence, whatever carries it needs to open its hand to its form, reach the height of its vulnerability, and blend in to germinate something else. In this passage where the act of creation is found, it keeps happening again and again, always different. This life=death=life∞ occurs both in each living being and in each other:

(…) life appears as a current that goes from germ to germ through the medium of a developed organism. Everything happens as if the organism itself were nothing more than an excrescence, a bud that the old germ makes to sprout as it works to prolong itself into a new germ. (BERGSON, 2019. p. 29)

Living beings are constantly changing, and the change lies in the passage from one germ to another, from which creation comes. Being made up of countless others in itself (cauliflower, bird, lion…), to a greater or lesser extent, the eggs are always there. We never stop being a seed, and “in the seed (and one could say in the genetic code), knowledge coincides with essence, life, potency and action itself” (COCCIA, 2018. p. 103).

Creation is the course of life in action (here the word “life” tries to express this current that passes between beings, a pulsating consciousness that circulates in all and is distinguished by the multiplicity of singular forms). An unimpeded action (without blocks, without barriers, without impediments) of both vibrating bodies and material bodies, and, above all, their integration – cells, stomach, chlorophyll, bones, phloem, nerves, parenchyma, leaves, skin, bark, nails, spines, feathers, scales, etc.; ways of being, thoughts, emotions, affections, gestures, languages, etc. In other words, however elusive and full of mysteries, however unknown they may be, vibrating/material bodies, with their vulnerability-forces, need to follow an unimpeded course of action to occur as creation. And, there is a knowledge in each singular being that indicates the paths that give way to creation, a knowledge in the measure of what is necessary, but that, without due care, is lost. This is how I have come across creation, and this experience leads me to confront Art (the one with a capital “A”), and how it institutionalized creation.

Art constituted itself as a discipline of knowledge by structuring the creative act in categories and classifications that, in principle, are just different languages – forms of expression created and adopted throughout the existence of living beings in different contexts. We can say that they are innate languages to the movements of life, of the actions of contact and exchange, and “the innate is an act, and an act without purpose, even if there are coincidences between the 'traces' of acting and some utility, which can even be indispensable for survival” (DELIGNY, 2015. p. 83). This creative act that expresses itself as language shows itself as “immanent articulation” (ROLNIK, 2011. p. 30) in/of collectives and societies. But the immanent articulation is blocked when the course of life in unimpeded action, that is, creation, is stagnant and stiffened, when it is millimetrically standardized, becoming a model to be reproduced – it is precisely at this node that I locate the invention of Art as institution. This knot separates creation from the everyday acts of life, and Art sustains exactly that by delimiting who, when and where creation can take place. Furthermore, in Art it is necessary for creation to result in a product, and for the products to conform to forms of circulation (which is quite different from the sharing of creation that takes place in contexts where immanent articulation is not blocked). In this way, I observe that the institutionalization of the creative act can generate the loss of its expressive vitality because it replaces the unimpeded action (essential for there to be creation) by the projection of the will (DELIGNY, 2015) – the desire to make a product according to standards and means of circulation. The will is not unfettered, it is linked to assumptions and expectations, and from there, the innate action is erased. After all, there is no “need to want in order to act. Quite the contrary: it is enough to want for the constellation that gives rise to action to disappear, a bit like the way the light of the sun makes the stars disappear” (Idem. p. 51). This cycle of Art generates distance from the knowledge that each living being has about its innate ability to create. Meanwhile, the creatures that weave webs teach us “that it is not a question, for the spider, of wanting, through the weaving of its web, to have flies; it's plotting that matters” (Ibidem. p. 65). And Lygia tells us:

Art constituted itself as a discipline of knowledge by structuring the creative act in categories and classifications that, in principle, are just different languages – forms of expression created and adopted throughout the existence of living beings in different contexts. We can say that they are innate languages to the movements of life, of the actions of contact and exchange, and “the innate is an act, and an act without purpose, even if there are coincidences between the 'traces' of acting and some utility, which can even be indispensable for survival” (DELIGNY, 2015. p. 83). This creative act that expresses itself as language shows itself as “immanent articulation” (ROLNIK, 2011. p. 30) in/of collectives and societies. But the immanent articulation is blocked when the course of life in unimpeded action, that is, creation, is stagnant and stiffened, when it is millimetrically standardized, becoming a model to be reproduced – it is precisely at this node that I locate the invention of Art as institution. This knot separates creation from the everyday acts of life, and Art sustains exactly that by delimiting who, when and where creation can take place. Furthermore, in Art it is necessary for creation to result in a product, and for the products to conform to forms of circulation (which is quite different from the sharing of creation that takes place in contexts where immanent articulation is not blocked). In this way, I observe that the institutionalization of the creative act can generate the loss of its expressive vitality because it replaces the unimpeded action (essential for there to be creation) by the projection of the will (DELIGNY, 2015) – the desire to make a product according to standards and means of circulation. The will is not unfettered, it is linked to assumptions and expectations, and from there, the innate action is erased. After all, there is no “need to want in order to act. Quite the contrary: it is enough to want for the constellation that gives rise to action to disappear, a bit like the way the light of the sun makes the stars disappear” (Idem. p. 51). This cycle of Art generates distance from the knowledge that each living being has about its innate ability to create. Meanwhile, the creatures that weave webs teach us “that it is not a question, for the spider, of wanting, through the weaving of its web, to have flies; it's plotting that matters” (Ibidem. p. 65). And Lygia tells us:

The impression I have is that we are going to make a big return and go back to that time when art was such an anonymous thing in life that there was no artist as a name or as a myth. People would create naturally, almost like an act of eating, of making love, of living, but without the concern of being the artist. (…) In my view, everyone potentially has the ability to create. Now, if a person is conditioned in an environment that does not favor him, he ends up not creating. And the blockade, the consumer society, the current conditioning, makes many people take this sensitivity and keep it to themselves. (THE WORLD…, 1973)

What would it be like to create naturally, almost like an act of eating? While I was studying Art, this type of question did not leave my orbit because my perception of creation was stuck on Art, but also because there was no favorable way to perceive that creation is in the act of living. Not having a favorable environment for such a life experience, but having favorable means to enter Art (at least to a certain extent), I tried to make this occupation a refuge to have space/time to create. Maybe Lygia went through something similar; it’s hard to know…

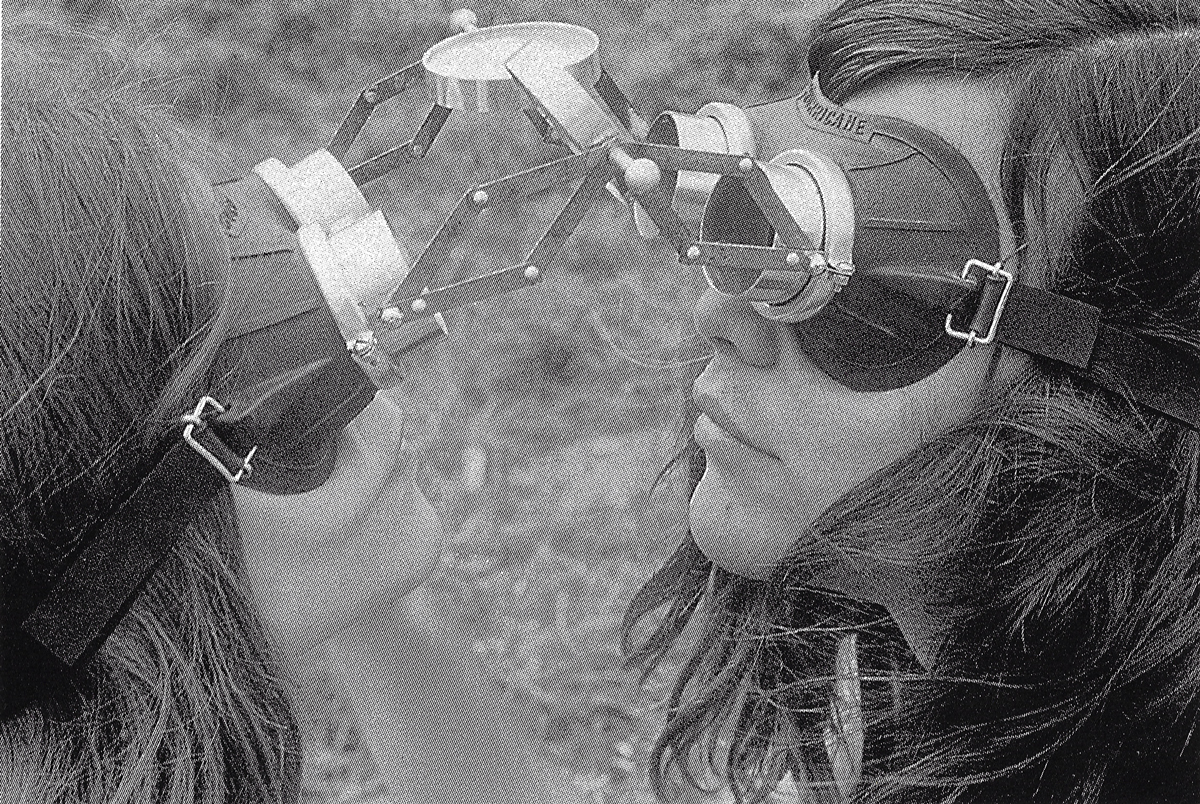

Elastic Net, 1973.

Photographs by Fátima Pombo

Not only does “everyone potentially have the ability to create,” everyone is creating, whether or not they are actively aware of the process. But the means that do not favor creation as an unimpeded action of life and the obstacles that arise from this can generate suffering. They are blocks that constrain life and, consequently, its expression, its languages. It happens that when we launch ourselves into Art, we can fall into a trivialization of suffering, since it is channeled in the “works,” through the refuge mentioned above. This prevents the opening of other paths for an exercise of care for such sufferings. Care that Art is not able to articulate, in which pain needs to be respected, needs to be listened to, and not idealized as a source of creation – “we have to get rid of the footprints of the romantic trap that combines creation with pain. Any situation in which life is constrained by the forms of reality and/or the way of describing them produces estrangement” (ROLNIK, 2011. p. 23-24). The estrangements we experience are part of life-changing movements, they are manifestations of vulnerability-force – the feast of life and death intertwined. Pain and suffering arise when this process is obstructed, but there are paths of care.

When Lygia says that she has the impression that we will make “a big return,” going back to a time when “art was a thing of life,” I believe that she is not talking about a nostalgia for specific ways of acting of other times and beings, but a reconnection with the exercise of a vital ethics that concerns “car[ing] for the preservation of life, which depends on the viability of the aesthetic experience to listen to its movements and adopt them as a beacon in the orientation of existence;” (Idem. p. 34).

When Lygia says that she has the impression that we will make “a big return,” going back to a time when “art was a thing of life,” I believe that she is not talking about a nostalgia for specific ways of acting of other times and beings, but a reconnection with the exercise of a vital ethics that concerns “car[ing] for the preservation of life, which depends on the viability of the aesthetic experience to listen to its movements and adopt them as a beacon in the orientation of existence;” (Idem. p. 34).

(…) expressing yourself better, loving better, eating better, that, deep down, interests me much more as a result than the thing itself that I propose to you. This is an exercise for life. (THE WORLD…, 1973)

The experience Structuring of the Self3 was an event that inaugurated a ritual that required leaving Art in order to activate a practice of care that, through the integration of bodily matter with various objects (little bags filled with air, water, sand or styrofoam; rubber tubes, cloths, socks, shells, honey, etc.), opens the way to the dynamic balance that keeps each living being actively involved in creation, in the exercise of life, and thus connected in the passage from one germ to another. And what is so potent about these objects? In the documentary Memory of the Body (1984), Lygia says: “I call this a relational object, because in reality it (...) only has a relationship with the subject, per se it has no quality whatsoever”. Perhaps we could say that nothing has quality per se, since the condition of being something or someone only happens in relation to (which included works of Art). So, what I recognize as potent not only in objects, but in the relationships established from the point of contact, is the presence of what I call life-forming agencies – water, earth, fire and air. Everything that is alive came to exist in this world from the interaction and mixture of these agencies, and Lygia summons them, directly or indirectly, in the objects she creates for the sessions – like the pebble that made grounding possible during the immaterial journey, or of its subtle breath directed to the body of whoever ventured into this ritual.

3 For a better understanding of what is both Structuring of the Self and Relational Objects, refer to the films mentioned in the bibliography.

The Relational Objects functioned as catalysts of the event that summoned the transvaluation of the living experience, that is, the valuation of life through a reconfiguration of the senses. I would like to call attention, then, not only to the emphasis that experience brings to the senses, but also to the fact that this is related to life-forming agencies. I believe that this contact between what exists primarily in common between bodies is the potential for a process of care, so that “the feast of the intertwining of life with death goes beyond the boundaries of art and spreads throughout existence” (ROLNIK). , 2015. p. 106). Lygia and the Relational Objects conducted the experience, but it was up to each participant to propagate not only the generated effects, but the very possibility of recomposing their contours and reestablishing their balance from encounters throughout life, expanding the “chances to realize this encounter in her own way, getting closer to her vibrating-body and exposing herself to her creative demands” (Ibidem. p. 105).

we would lie down and she would put some weights with different textures, things on points of the body, and leave them there for a while. And you didn't know if it was a bag of sand, then water, then with small pebbles. She massaged them a little, but most she left alone, just touching. Some things were very indirect, like, for example, she would take a thin straw and blow from afar.4

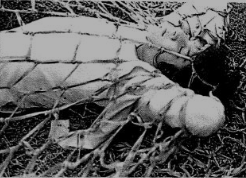

Lygia’s propositions “release a lot of raw materials that we have inside us”5 – this raw material is nothing more than the portion of life-forming agencies that make up all bodies, including Relational Objects. Remaining in silence and solitude with these materialities in contact with the body generated a fusion: “everything disappears and you merge with the Object. (…) it is an exchange with the Object, indescribable,”6 and this is shown as a process of creating a language that emerges from this fusion. Lula Wanderley reports that he went through an unblocking of his vital activity, and “this feeling of life unblocking is difficult to put into words, this you will put into life.”7 It is an unblocking of the unimpeded action of life, of the creative power and of the active consciousness to its processes, and, consequently, of the expression of singular languages in/of each being, which can become part of the immanent articulation in/of societies.

4 Caetano Veloso in an interview with Suely Rolnik, published on DVD in Archive for a Work-Event, 2011.

5 Lia Rodrigues in an interview with Suely Rolnik, published on DVD in Archive for a Work-Event, 2011.

6 Lula Wanderley in an interview with Suely Rolnik, published on DVD in Archive for a Work-Event, 2011.

7 Idem.

5 Lia Rodrigues in an interview with Suely Rolnik, published on DVD in Archive for a Work-Event, 2011.

6 Lula Wanderley in an interview with Suely Rolnik, published on DVD in Archive for a Work-Event, 2011.

7 Idem.

Listening to the reports of some of the people who participated, I realize that the experience affected the feeling of vibrating/material contour. The fusion with Relational Objects could soften existential contours that are too rigid, fixed in pre-established patterns of subjectivity. But contact with the objects could also trigger contour formation, strengthen the subjective structure of people in existential states that are too diluted, which, without consistency, lose the power of action. As Lula Wanderley (2011. p. 23) observes: “The body in Lygia Clark becomes an experience in which a dynamic totality – body/subject+object/world – crosses the void of a cosmic dissolution and, paradoxically, reaffirms difference, individuation.”

Canibalism, 1973.

Photograph by Fátima Pombo

Once it unlocks vital activity, the process causes the germination of languages. As I highlighted above, what came to be called Art is nothing more than the categorization of the languages innate to the movements of life, of the expressions that generate contact and exchange, and, once Lygia's proposition awakens this power, it extrapolates the place of Art, also extrapolating the hegemonic language that is established in the intelligible interpretations of words. They are languages that access a vibrating/material reality that is not trapped in the word – the sensorial reality. The sensorial is the dimension of contact with the ecology of life, with the cosmos; they are organic mechanisms that primarily enable the creation of an existential contour, a contour that remains connected with the multiple dimensions of what is alive. This sensorial reality is one of the ways through which we know what we are, know our limits, and it is also "how we understand everything that we are not. Seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching are the five ways - the only five ways – through which the universe can communicate with us" (GRANDIN, 2020. p. 78 – author's emphasis), any other way comes from there. Sensorial senses generate a rhythm between creating contour and merging with the cosmos. They are activated when a living being creates a body outside of the seed, and they work in interaction, an interdependence, in the many ways that this can appear (balancing itself when there is a blockage). But, once outside the seed, context can cause a weakening of this network, by intending to replace it with other languages (such as words when they are vectors of rigid and hierarchical categorizations) in the action of generating and maintaining the necessary contours for vital relationships. From this, I think especially about the care practices of “existential territories” (GUATTARI, 1990), focusing attention on the relationship between the sensorial and the word: it is not that the word blocks the sensorial senses to the point of eliminating them – the word can generate a specific type of knowledge about oneself and about the world that adds to the sensorial. But when this learning is glued to the pretense of overcoming sensorial senses, its divisive and non-aggregative, or integrative, action becomes clear, and this is crucial when we are aiming for care.

In this split context, the word and the sensorial are two distinct mechanisms of sensation of oneself, which trigger processes of singularization with which it is possible to recognize oneself, to know one’s power as a living being, and to know the world – and “there is no way to separate the 'self' from the context.” However, these two operations must be one and the same operation; the word alone is not capable of keeping us integrated in the vital current that passes between beings (life as a pulsating consciousness that circulates), since the sensorial senses are innate (among the multiple manifestations), thus, it is necessary that the word exists as an ally of the sensorial, so that the beings that transit through it remain integrated. That is why rituals such as the one proposed by Lygia are important care practices in environments that are not favorable to creation, such as colonial and racializing capitalism with its fixation on categories, as they seek to rescue the wisdom of the self from the sensorial in the contact with “raw materials,” without relying on words, but rebalancing and reintegrating this operation that had previously separated into two. But it's not about giving up on Art, it's about remembering that creation is not stuck to it; it's a free action intrinsic to the exercise of life and its care processes. For Art to be a creation (then spelled with a lowercase ‘a,’ like other acts of living, such as eating, making love…) an ethical commitment to life is therefore necessary.

I conclude by sharing that in my experience of creation and care, this process has proved to be essential, and my meetings with Lygia have been catalysts and promotions of the opening necessary to unlock vital activity and expose myself to the unique requirements of creating my vibrating/material body. This is the invitation of Lygia's creations, and it is the invitation of this text.

I conclude by sharing that in my experience of creation and care, this process has proved to be essential, and my meetings with Lygia have been catalysts and promotions of the opening necessary to unlock vital activity and expose myself to the unique requirements of creating my vibrating/material body. This is the invitation of Lygia's creations, and it is the invitation of this text.

Text written from the research and elaboration of my doctoral thesis supervised by Suely Rolnik, at the Center for Studies of Subjectivity, of the Postgraduate Program in Clinical Psychology, at PUC SP. Currently scheduled to finish in June 2022.

jialu pompo

A doctoral student in Clinical Psychology at PUC SP, I research clinical processes and the creation of languages as ways to decolonize life of binary structure. Graduation and Master's degree in Visual Arts UFRJ. As someone who is neurodivergent and gender dissident, I participate and carry out activities that cross these themes and art.

jialu pompo

A doctoral student in Clinical Psychology at PUC SP, I research clinical processes and the creation of languages as ways to decolonize life of binary structure. Graduation and Master's degree in Visual Arts UFRJ. As someone who is neurodivergent and gender dissident, I participate and carry out activities that cross these themes and art.

Bibliographic References

BERGSON, Henri. The Creative Evolution. Translation into Portuguese by Bento Prado Neto. – 2nd ed. São Paulo: Editora WMF Martins Fontes, 2019. - (Library of Modern Thought)

COCCIA, Emanuele. The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture. Translation into Portuguese by Fernando Scheibe – Desterro [Florianópolis]: Cultura e Barbárie, 2018.

DELIGNY, Fernand. The Arachnian and Other Texts. Translation into Portuguese by Lara de Malimpensa. São Paulo: n-1 edições, 2015.

DISERENS, Corinne; ROLNIK, Suely. Lygia Clark: From Work to Event. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo Organização Social, 2006.

GUATTARI, Félix. The Three Ecologies. Translation into Portuguese by Maria Cristina F. Bittencourt; Revision of the translation by Suely Rolnik. 2nd edition. Campinas: Papirus, 1990.

GRANDIN, Temple; PANEK, Richard. The Autistic Brain. Translation into Portuguese by Cristina Cavalcanti. 12th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2020.

ROLNIK, Suely. Archive for a Work-Event: A Project to Activate the Body Memory of an Artistic Trajectory and Its Context. São Paulo: Selo Sesc, 2011.

GUATTARI, Félix. The Three Ecologies. Translation into Portuguese by Maria Cristina F. Bittencourt; Revision of the translation by Suely Rolnik. 2nd edition. Campinas: Papirus, 1990.

GRANDIN, Temple; PANEK, Richard. The Autistic Brain. Translation into Portuguese by Cristina Cavalcanti. 12th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2020.

ROLNIK, Suely. Archive for a Work-Event: A Project to Activate the Body Memory of an Artistic Trajectory and Its Context. São Paulo: Selo Sesc, 2011.

____________. Sentimental Cartography: Contemporary Transformations of Desire. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 1989.

____________. Lygia Clark and the Hybrid Art/Clinic. Revista concinnitas, year 16, v. 01, n 26, july of 2015. p. 104-112. Available at https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/ojs/index.php/concinnitas/article/view/20104. Acessed on Sept. 2017.

WANDERLEY, Lula. In the Silence that Words Keep; organized by Kaira M. Cabañas. São Paulo, SP: n-1 edições, 2021.

Videographic References

ARCHIVE for a Work-Event: A Project to Activate the Body Memory of an Artistic Trajectory and Its Context. Direction and interviews: Suely Rolnik. São Paulo: DVD, Selo Sesc, 2011.

THE WORLD of Lygia Clark. Direction: Eduardo Clark. Rio de Janeiro: [s. n.], 1973. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCohXfwFlz4 . Acessed on: Sept. 13, 2020.

MEMORY of the Body. Direction: Mário Carneiro. Rio de Janeiro: [s.n.], 1984. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3VU6KtfhSI. Acessed on: Oct. 30, 2021.