Of glass. Why does it not recoil, or die?

Laila Terra

Title:

FARNSWORTH, Edith. “Artifact”. Memoirs. Chicago: Newberry Library Archives.

Initial note

I start the note with the “Theory of knots”. We can define knots in our daily lives: shoelaces, strands of hair, sailors’ ropes. A continuous tying of a thread or threads to themselves using internal folds. In knot theory in the study of mathematics, knots have their ends united and cannot be undone. In the register, any given knot can be drawn in many ways using a knot diagram. This article was written in July 2020, and in November 2021, the “Farnsworth House” institution changed its name and that of the architectural work to the name “Edith Farnsworth House”. According to the website, a historic reparation acknowledging Edith's importance in creating the house for which she commissioned architect Mies van der Rohe. In the article “Memory, forgetting, silence” by Michael Pollak, written in 1989, the author focuses on the subterranean memories of the excluded, of minority and marginalized groups, memories that emerge in opposition to an “official memory”. According to the author, subterranean memories, as a fundamental part of dominated cultures, survive silently, emerging in crises and favorable political contexts and entering into dispute with “official” memory. In this perspective, it is worth asking: how was the “official” story of the “Edith Farnsworth House” told until November 2021? How is it being told today? The Farnsworth House is a myth built by “men” for “men” – as Edith comments in her diaries. Edith Farnsworth's poems contribute to a perception of beauty. The glass house appears in the works not as a backdrop or neutral object, it is the “subject” that provides experiences and contemplations, that activates events. The poems evaluate the transitory events that the house provides. Edith's subterranean memories have silently survived to the present day and emerge opening a dispute with the "official" memory: from the "unsaid" to contestation and claim.

I start the note with the “Theory of knots”. We can define knots in our daily lives: shoelaces, strands of hair, sailors’ ropes. A continuous tying of a thread or threads to themselves using internal folds. In knot theory in the study of mathematics, knots have their ends united and cannot be undone. In the register, any given knot can be drawn in many ways using a knot diagram. This article was written in July 2020, and in November 2021, the “Farnsworth House” institution changed its name and that of the architectural work to the name “Edith Farnsworth House”. According to the website, a historic reparation acknowledging Edith's importance in creating the house for which she commissioned architect Mies van der Rohe. In the article “Memory, forgetting, silence” by Michael Pollak, written in 1989, the author focuses on the subterranean memories of the excluded, of minority and marginalized groups, memories that emerge in opposition to an “official memory”. According to the author, subterranean memories, as a fundamental part of dominated cultures, survive silently, emerging in crises and favorable political contexts and entering into dispute with “official” memory. In this perspective, it is worth asking: how was the “official” story of the “Edith Farnsworth House” told until November 2021? How is it being told today? The Farnsworth House is a myth built by “men” for “men” – as Edith comments in her diaries. Edith Farnsworth's poems contribute to a perception of beauty. The glass house appears in the works not as a backdrop or neutral object, it is the “subject” that provides experiences and contemplations, that activates events. The poems evaluate the transitory events that the house provides. Edith's subterranean memories have silently survived to the present day and emerge opening a dispute with the "official" memory: from the "unsaid" to contestation and claim.

POLLAK, Michel. Memória, esquecimento, silêncio. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, vol 2, n 3, 1989, pag 3-15.

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

In this essay, we venture to explore the hypothesis that architecture, in addition to being a domain of cultural expression that guards and conserves myths, is also a field of production and reproduction of them.

When investigating the surroundings of the process that resulted in the creation of the already renowned architectural work "Farnsworth House" by Mies van der Rohe in 1951, we find contrasting ethical-poetic points of view. The first, which we take as classical since it dominates common understanding, is what the official website of the work discloses, reports, what we will call “official,” that which has been held since the development of the project and its subsequent memorialization, descriptive of the stages of the house from conception to construction to completion and which have been cited and commented upon both in relevant sector magazines and in critical texts specializing in modern and/or contemporary architecture.

In contrast to this perspective, there is an extensive archive in respect to Edith Farnsworth's life, with documents, diaries, notebooks, annotated photos, impressions and unique testimonies about the "Farnsworth House". This material is maintained and preserved at the Chicago Public Library. It is little publicized. Consultation of it is limited and restricted to Americans. For the rest of the world, we only have access to a digitized portion of the material made available on the institution's website. This second landscape, dismissed by the "official" representatives of the work, is undervalued. It is a minority view, which asserts itself in the singularity of that which escapes the discursive spotlight of the prevailing culture. The look is that of a woman, single, intellectual, autonomous, imperceptible categories in a world dominated by arbitrary, dogmatic and idealistic projects. What is at stake in the opposition between two points of view is the movement that carries with it the truths of indisputable propositions and breaks their dogmatic structures. At this point, we glimpse the paradigm of modernist architectural works.

This raises some questions. Should the houses/artistic works be inhabited and, consequently, be transformed by those who reside in them? Or, on the contrary, should they remain as one-to-one scale models and be experienced only as poetic installation pieces? Would they fulfill their purpose of home/residence without being lived in? Or, put another way, would the experiences from the encounters between inhabitant bodies and the houses’ own bodies turn the houses into true poetic works?

The official discourse of the Farnsworth house began to be created before the house even existed. Since its first appearance in model form in 1947 at the MoMA exhibition in New York, the architectural world already considered it an authentic rational creation. Phillip Johnson, curator of the exhibition writes:

When investigating the surroundings of the process that resulted in the creation of the already renowned architectural work "Farnsworth House" by Mies van der Rohe in 1951, we find contrasting ethical-poetic points of view. The first, which we take as classical since it dominates common understanding, is what the official website of the work discloses, reports, what we will call “official,” that which has been held since the development of the project and its subsequent memorialization, descriptive of the stages of the house from conception to construction to completion and which have been cited and commented upon both in relevant sector magazines and in critical texts specializing in modern and/or contemporary architecture.

In contrast to this perspective, there is an extensive archive in respect to Edith Farnsworth's life, with documents, diaries, notebooks, annotated photos, impressions and unique testimonies about the "Farnsworth House". This material is maintained and preserved at the Chicago Public Library. It is little publicized. Consultation of it is limited and restricted to Americans. For the rest of the world, we only have access to a digitized portion of the material made available on the institution's website. This second landscape, dismissed by the "official" representatives of the work, is undervalued. It is a minority view, which asserts itself in the singularity of that which escapes the discursive spotlight of the prevailing culture. The look is that of a woman, single, intellectual, autonomous, imperceptible categories in a world dominated by arbitrary, dogmatic and idealistic projects. What is at stake in the opposition between two points of view is the movement that carries with it the truths of indisputable propositions and breaks their dogmatic structures. At this point, we glimpse the paradigm of modernist architectural works.

This raises some questions. Should the houses/artistic works be inhabited and, consequently, be transformed by those who reside in them? Or, on the contrary, should they remain as one-to-one scale models and be experienced only as poetic installation pieces? Would they fulfill their purpose of home/residence without being lived in? Or, put another way, would the experiences from the encounters between inhabitant bodies and the houses’ own bodies turn the houses into true poetic works?

The official discourse of the Farnsworth house began to be created before the house even existed. Since its first appearance in model form in 1947 at the MoMA exhibition in New York, the architectural world already considered it an authentic rational creation. Phillip Johnson, curator of the exhibition writes:

The Farnsworth house with its continuous glass walls is an even simpler interpretation of an idea. Here the purity of the cage is undisturbed. Neither the steel columns from which it is suspended nor the independent floating terrace break the taut skin.1

In a brief report, Edith Farnsworth, who was also present at the opening of the exhibition, demonstrates the pride she felt for the project, thanks to its role in the cultural scene of the time.

Fiquei feliz quando embarquei no trem de volta para Chicago, refletindo que nosso projeto poderia muito bem vir a se tornar o protótipo de novos e importantes elementos da arquitetura americana.2

2

Friedman page 134. In WENDL.

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

An important detail stands out in Farnsworth's words. She refers to the creation of the project as “our project.” This leads us to the understanding that, for her, her participation in the design of the project was unequivocal and, therefore, the authorship would be collective, born of the link established between Mies' ideas, as an architect, and hers, as a contractor.

In both reports, we can see enthusiasm for the project for its effectively innovative character regarding notions of domestic character within architecture. It would be the first house that would transport materials and techniques, such as steel and glass, from large industrial and business buildings, founded on economic-based logistics, to the private domestic plane.

***

From the confrontation of the two discursive points of view presented, differences arise that refer directly to the distinction between the ideological plane and the plane of the real. It is a divergence of nature, which differentiates the essences of each perspective: from the modernist project, as it has been officially publicized; and the sensorial experience, as shown by the records of the experiences of those who lived in the house for twenty years. It is necessary to understand more than the elementary set that makes the Farnsworth House an aesthetic sign. It is necessary to enter the historical context of the language that encompasses this specific sign, because every language is consigned to a certain time and space. It is necessary to identify the discourse ascribed to the house and to the characters who occupied it in the different situations. Who was Mies van der Rohe when he was hired by Edith, and what were the enunciations concerning him? Who was Edith Farnsworth, the contractor, and how was she represented by history (from 1940 to 2020)? When was the house designed and where? What are the constructive elements proposed by Mies? What was Edith's reaction after the house was finished and what did that entail? And, finally, what happened to the house over time (from 1951 to 2020)? Finally, with these data, we can confront the discourses.

Mies was born in Germany in 1886. He inherited from his father, a stonemasonry professional, the knowledge about working with rocks, which helped him in the development of his modernist projects. In 1930, he was invited to be director of the Bauhaus, during which time he designed the German pavilion exhibited at the World’s Fair in Barcelona (1932). Due to the political situation in Germany, in 1933 Mies went to the United States and arrived there with the status of great architect of the new modernity. The Americans welcomed him enthusiastically. Post-World War I America was growing industrially and seeking recognition in the world's cultural output.

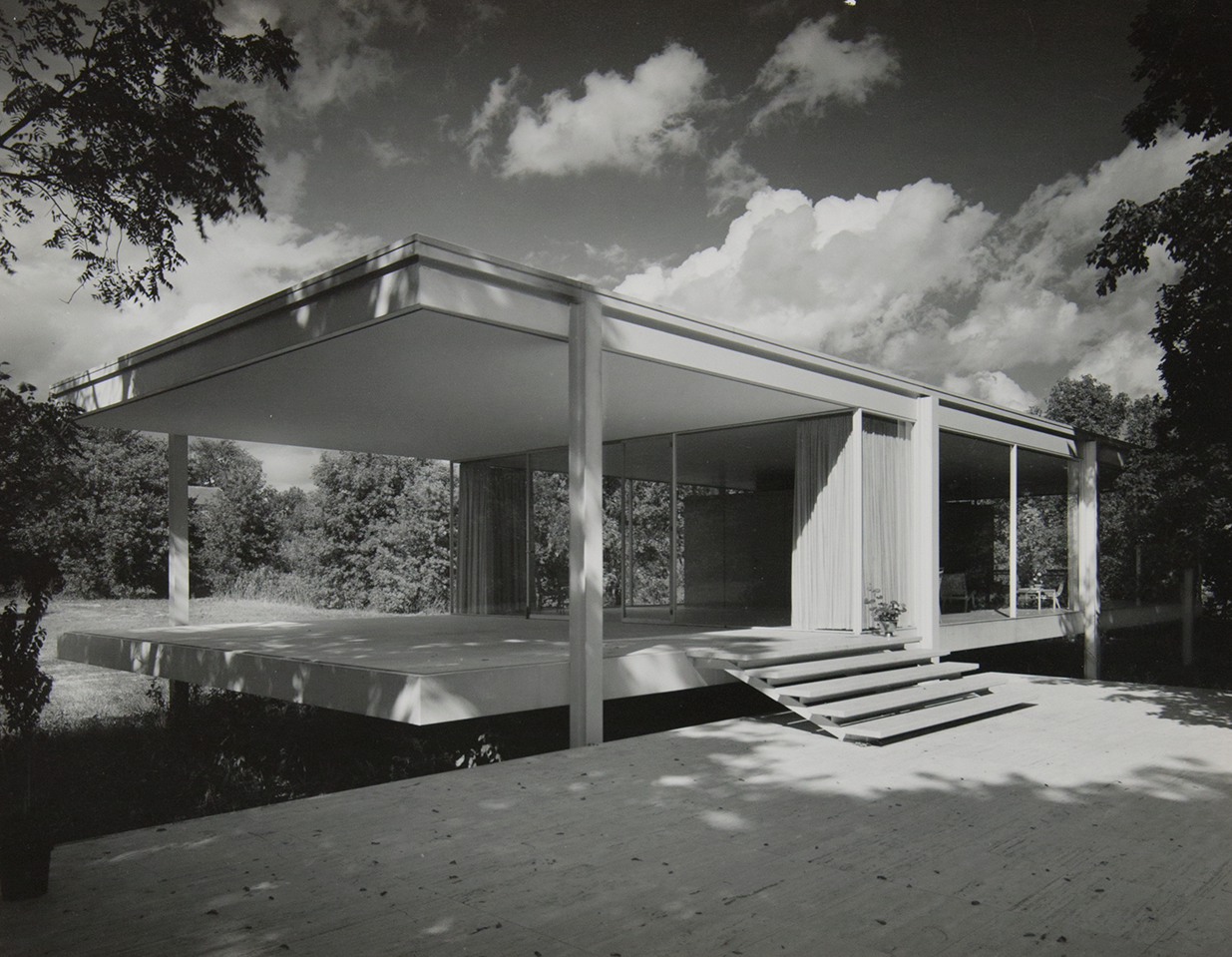

It is within this context that he receives the commission and designs Farnsworth House. The work was built between the years 1950 and 51 with important modifications to the original project of 1947. The house was built 30 meters from the bank of the Fox River, in the city of Plano, in the state of Illinois. True to his principles, Mies designed a 9 by 23 meter cobblestone, built as a stilt 1.5 m above the ground, to withstand the floods of the river. The one-story house consists of an external steel structure with eight pillars (I-beams). The structural I-beams are at the same time aesthetically expressive. Between them, connecting the floor to the ceiling and surrounding the entire house, large glass panels were placed. This opened the environment to the surrounding landscape.

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

The geometric shape utilized by the architect proposed to generate a centrifugal relationship with nature. His proposal aimed to build a shelter in its simplest state. As stated by Mies:

If you view nature through the glass walls of the Farnsworth House, it gains a more profound significance than if viewed from the outside. That way more is said about nature---it becomes part of a larger whole.

3

3 Mies van der Rohe. In FRACALOSSI.

The only walls of the house are those of a small central module containing the structures of the bathrooms, kitchen and fireplace, hydraulic parts, sewage and energy. On the official website of the house, we find the following opening text:

The Edith Farnsworth House is one of the most significant of Mies van der Rohe’s works, equal in importance to such canonical monuments as the Barcelona Pavilion, built for the 1929 International Exposition and the 1954-58 Seagram Building in New York. Its significance is two-fold. First, as one of a long series of house projects, the Edith Farnsworth House embodies a certain aesthetic culmination in Mies van der Rohe’s experiment with this building type. Second, the house is perhaps the fullest expression of modernist ideals that had begun in Europe, but which were consummated in Plano, Illinois. As historian Maritz Vandenburg has written in his monograph on the Edith Farnsworth House: “Every physical element has been distilled to its irreducible essence. The interior is unprecedentedly transparent to the surrounding site, and also unprecedentedly uncluttered in itself. All of the paraphernalia of traditional living –rooms, walls, doors, interior trim, loose furniture, pictures on walls, even personal possessions – have been virtually abolished in a puritanical vision of simplified, transcendental existence. Mies had finally achieved a goal towards which he had been feeling his way for three decades.”

4

This text begins by placing the house at the level of an iconic work, even before describing the format, material, period and size. And places it as one of the architect’s three main works. It uses a description by Maritz Vanderburg, historian and founder of Architecture and Technology Press, of 2005, to theoretically justify the house as a symbol of modernist architecture. In the description, the tone elevates the work to something beyond the functionality of a home. All the belongings of a family, or people who would probably occupy the environment, were called “paraphernalia” and, according to him, were abolished, giving the house the status of a museological work of art, respecting North American Puritan traditions.

That was what the house was like. All open, transparent, so that life in it was immanent to nature and nature to it. It is immediately apparent that Mies begins to use the task of creating the house to shape his own vision of modernity. By ignoring the specific requests of his client, the project becomes for him an experiment in architecture of his conception of modernity. Despite the controversies surrounding the construction, the architectural world would welcome Farnsworth House with great enthusiasm. It would express the newest open-plan principle, initially proposed by Le Corbusier.

In contrast to this view, we have that of the contractor. Edith was a very successful doctor, a researcher in nephrology. Her experimental efforts at Northwestern University produced breakthroughs against renal nephritis. She also majored in English Literature and Composition at the University of Chicago. The results of her studies are contained in three boxes of notebooks at the Chicago Public Library, filled with insights and poetic accounts in journal form. Edith was an independent woman, an intellectual who liked to frequent cultural environments of the so-called new modernity. In 1945, during a dinner party, she meets Mies and invites him to design a country house for her on land she owned on the bank of the Fox River. Edith was far from imagining that this construction would bring her frustrations, the value of the work exceeding 33 thousand dollars, which motivated her to start a lawsuit, which she would lose in the end.

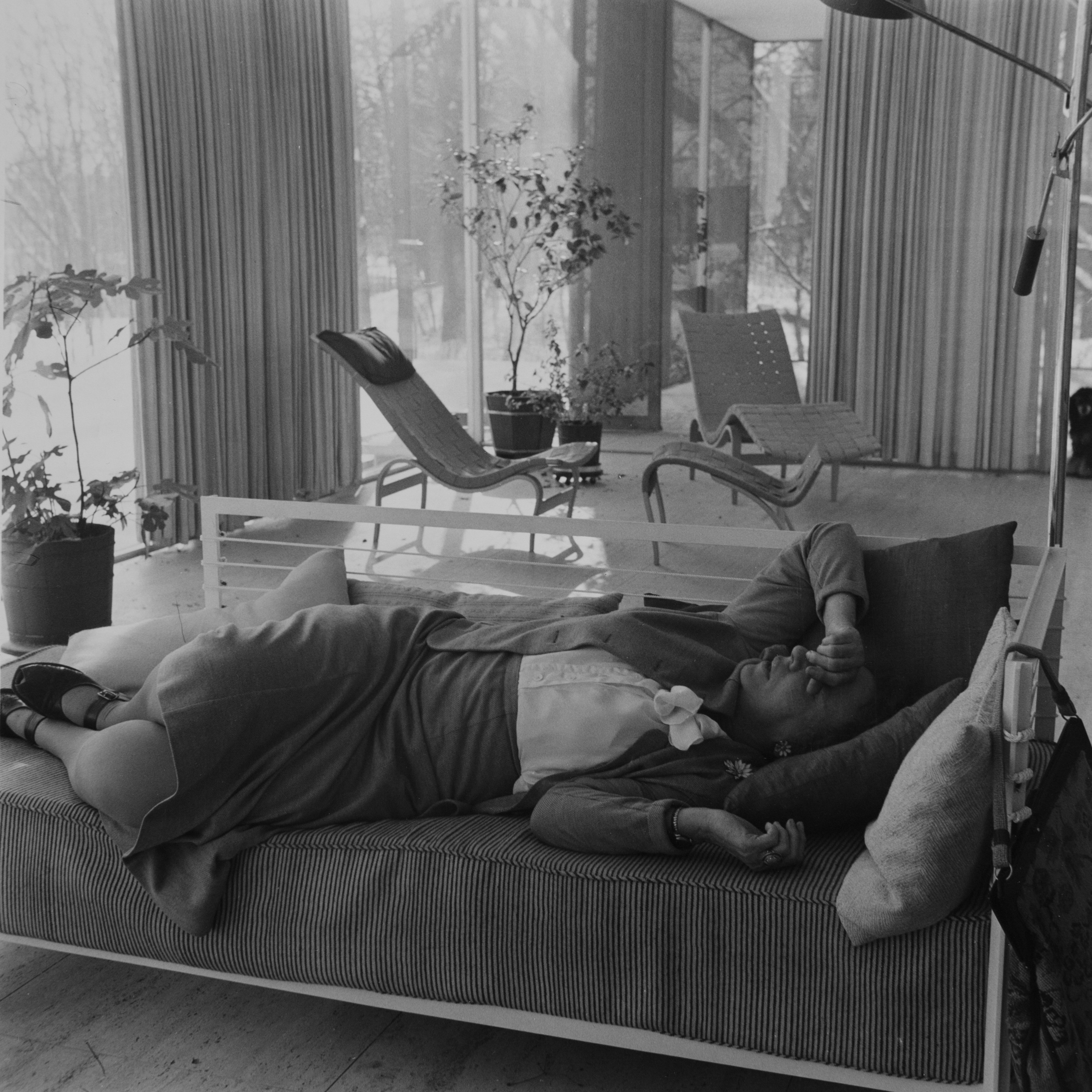

When Edith moved into the house in December 1950, the roof leaked and the heating produced a film of steam that condensed inside the glass walls. According to Farnsworth, the house was uninhabitable, was open to mosquitoes, had no privacy, had ventilation problems, including in relation to the fireplace, and did not have the comfort she wanted for a country house, where she could invite friends without having to put a mattress on the floor. In her memoirs, Edith vividly describes her experience with the house. In the account below, Dr. Farnsworth reflects on her early experiences with it after it had just been built. We see a contradiction between the discourse that was made official, which idealizes the steel and glass structure, and the resident's perceptions.

That was what the house was like. All open, transparent, so that life in it was immanent to nature and nature to it. It is immediately apparent that Mies begins to use the task of creating the house to shape his own vision of modernity. By ignoring the specific requests of his client, the project becomes for him an experiment in architecture of his conception of modernity. Despite the controversies surrounding the construction, the architectural world would welcome Farnsworth House with great enthusiasm. It would express the newest open-plan principle, initially proposed by Le Corbusier.

In contrast to this view, we have that of the contractor. Edith was a very successful doctor, a researcher in nephrology. Her experimental efforts at Northwestern University produced breakthroughs against renal nephritis. She also majored in English Literature and Composition at the University of Chicago. The results of her studies are contained in three boxes of notebooks at the Chicago Public Library, filled with insights and poetic accounts in journal form. Edith was an independent woman, an intellectual who liked to frequent cultural environments of the so-called new modernity. In 1945, during a dinner party, she meets Mies and invites him to design a country house for her on land she owned on the bank of the Fox River. Edith was far from imagining that this construction would bring her frustrations, the value of the work exceeding 33 thousand dollars, which motivated her to start a lawsuit, which she would lose in the end.

When Edith moved into the house in December 1950, the roof leaked and the heating produced a film of steam that condensed inside the glass walls. According to Farnsworth, the house was uninhabitable, was open to mosquitoes, had no privacy, had ventilation problems, including in relation to the fireplace, and did not have the comfort she wanted for a country house, where she could invite friends without having to put a mattress on the floor. In her memoirs, Edith vividly describes her experience with the house. In the account below, Dr. Farnsworth reflects on her early experiences with it after it had just been built. We see a contradiction between the discourse that was made official, which idealizes the steel and glass structure, and the resident's perceptions.

By the end of 1950, it seemed possible to spend a night in the house, and on New Year’s Eve I brought out a couple of foam mattresses and a number of other indispensible articles and prepared to inhabit the glass house for the first time. With the light of a bare, sixty-watt bulb on an extension cord I made up the foam rubber mattress on the floor, turned up the air furnaces and got something to eat. Spots and strokes of paint remained here and there on the expanses of the glass walls and the sills were covered with ice. The silent meadows outside, white with old and hardened snow, reflected the bleak bulb within, as if the glass house itself were an unshaded bulb of uncalculated watts lighting the winter plains. The telephone rang, shattering the solitary scene.

It was an uneasy night, partly from the novel exposure provided by the uncurtained glass walls and partly from the dread of Mies’ implacable intentions. Expenses in connection with the house had risen far beyond what I had expected or could well afford and the glacial bleakness of that winter night showed very clearly how much more would have to be spent before the place could be made even remotely inhabitable.

It was an uneasy night, partly from the novel exposure provided by the uncurtained glass walls and partly from the dread of Mies’ implacable intentions. Expenses in connection with the house had risen far beyond what I had expected or could well afford and the glacial bleakness of that winter night showed very clearly how much more would have to be spent before the place could be made even remotely inhabitable.

5

Edith Farnsworth. Memórias, cap. 13 – sem página. In WENDL.

Edith was so upset with the house that, in addition to starting a legal fight, which she lost and was forced to pay the costs of the process, she dedicated herself to denouncing the house in one of the magazines most read by the non-specialized public of that time.

In the article “The Threat to the Next America”, the editor Elizabeth Gordon takes Edith's side and ends up denouncing the architect and his work: “I have decided to speak up” (Gordon, 1953: 126). For her, there was a “dictatorial culture” that placed the personal intimacy of the home at the expense of a new aesthetic of steel and glass. The line between acceptable and unacceptable modernism, according to Gordon, seemed to depend on the pace of "elimination of partition walls so that a house tends to be one public room with open areas for sleeping, eating, playing, etc." to “maximum use of glass without any corrective devices for shade or privacy”. Modernist architecture implies, as Gordon suggests, an excessive "trip" that requires "corrective mechanims" to become social.

In an article publisheed in 1953 in House Beautiful magazine, Gordon was committed to destroying the image of Mies and the modern architecture also known as the International Style (name given in 1932), opening a public debate over the right of European modernism to conquer the home of the American countryside. She considered the Farnsworth House project “bad modern architecture” and, with aggressive and xenophobic words, she described Mies van der Rohe as a totalitarian of German origin, who tried to impose his fascist ideas on a liberal America.

Gordon devoted two issues of the magazine to denouncing the International Style. In the first edition, the editor spares Mies and Edith, making a more generalized critique of this new architecture. In the next issue, the magazine features an interview with Edith Farnsworth, in which she recounts the process of building the house and her current relationship with the work.

In the article “The Threat to the Next America”, the editor Elizabeth Gordon takes Edith's side and ends up denouncing the architect and his work: “I have decided to speak up” (Gordon, 1953: 126). For her, there was a “dictatorial culture” that placed the personal intimacy of the home at the expense of a new aesthetic of steel and glass. The line between acceptable and unacceptable modernism, according to Gordon, seemed to depend on the pace of "elimination of partition walls so that a house tends to be one public room with open areas for sleeping, eating, playing, etc." to “maximum use of glass without any corrective devices for shade or privacy”. Modernist architecture implies, as Gordon suggests, an excessive "trip" that requires "corrective mechanims" to become social.

In an article publisheed in 1953 in House Beautiful magazine, Gordon was committed to destroying the image of Mies and the modern architecture also known as the International Style (name given in 1932), opening a public debate over the right of European modernism to conquer the home of the American countryside. She considered the Farnsworth House project “bad modern architecture” and, with aggressive and xenophobic words, she described Mies van der Rohe as a totalitarian of German origin, who tried to impose his fascist ideas on a liberal America.

Gordon devoted two issues of the magazine to denouncing the International Style. In the first edition, the editor spares Mies and Edith, making a more generalized critique of this new architecture. In the next issue, the magazine features an interview with Edith Farnsworth, in which she recounts the process of building the house and her current relationship with the work.

There are too many practical things they (Mies disciples) refuse to consider. For instance, Mies wanted the partition closet five feet high for reasons of ‘art and proportion.’ Well, I’m six feet tall. Since my house is all ‘open space,’ I needed something to shield me when I had guests.

I wanted to be able to change my clothes without my head looking like it was wandering over the top of the partition without a body. It would be grotesque.6

I wanted to be able to change my clothes without my head looking like it was wandering over the top of the partition without a body. It would be grotesque.6

6 Gordon, 1953: 129. In PRECIADO.

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

The conflict was triggered in such a way that criticism was directed at Edith. And, in this context, even though she was a doctor and an academic – a choice that put her at odds with the social expectations of women in the 1940s and 1950s – the recriminations were targeted at her image. Despite a challenging and prodigious career, Farnsworth always expressed unease in relation to disapproving looks and was well aware that she was outside society's standards, but she never failed to minutely question the mores she was expected to conform to. Her relationship with Mies could also be interpreted this way: she was looking for an intellectual relationship, rather than a romantic partner, and became disillusioned; “Perhaps it was never a friend and a collaborator, so to speak, that he wanted,” she writes, “but a dupe and a victim.” Edith’s disillusionment contrasts with the image she had created upon her return from the New York exhibition. The principle of collaboration seems to have been just an illusion.

These references are important, according to Kathleen LaMoine Corbett. In her doctoral thesis, Tilting at Modern: Elizabeth Gordon's “The Threat to the Next America”, she raises issues related to the genre that permeate the discourses about Farnsworth House, especially those present in the first biography of Mies van der Rohe, written by Franz Schulze, and those declared in the repercussions to the two articles published in House Beauty magazine in 1953. It is important to identify Franz Schulze's aggressive misogyny when describing Edith, due to her contestation in relation to the - male - architect and his work.

“Edith, was no beauty. Six feet tall, ungainly of carriage, and, as witnesses agreed, rather equine in features, she was sensitive about her physical person and may very well have compensated for it by cultivating her considerable mental powers.” Edith is presented at a threshold between femininity, masculinity, and animality – a space occupied by the vampire and the lesbian– as a woman of excessively strong and threatening features. As an urban Amazon woman deprived of her horse, Edith seems to be possessed by animal characteristics.

7

7

Schulze (1985, p. 258) in PRECIADO

In this text by Schulze, the construction of imagery of the characters is unequivocally constituted by intentions – as the French author Roland Barthes proposes when he states that myths have an ideological nature. Edith, who was an extremely intelligent woman, important in the field of medicine at the time, was described as a villain or the shrew of children's tales. She was judged on an inappropriate and malicious androcentric criterion, based solely on the effect of her physical appearance. In his text, Schulze portrayed her as an aberration who was compensated with threats and intellectual blackmail. He distorted the cause of her frustration with the house, implying that the reason was heartbreak suffered on account of the architect.

![]()

Mies appears in the story as a man "of great charm and charisma", while Edith "was painfully lonely, bored and overwhelmed" (Friedman, 1998: 131). According to biographers and essayists of that time, Edith's denunciation had nothing to do with the quality of the project, it was a reaction motivated by resentment arising from her amorous frustration. It was this version that became popular with the publication and dissemination of Mies Van Der Rohe - A Critical Biography - Franz Schulze. He quotes Van der Rohe himself, though he never investigated the circumstances or the accuracy of the account: “The old maid that would have wanted ‘the architect to come with the house’" (Schulze, Mies van der Rohe, 253).

Farnsworth House is a United States National Historic Landmark as a masterpiece of modern architecture. It transposes immateriality, made for immaterial residents. Its furniture is well ordered and designed - this is the text we read when we open the house's official website, an expression of the genius of a man who has the ability to materialize a spectral structure for immaterial inhabitants.

If we understand that the architecture of Farnsworth House is as much made up of steel, glass and cement, as it is of the myths that propelled it into existence, we can say that it is the first “domestic glass box” in history, with all that that can mean in terms of a rationalist model of existence. Its materials and design carry a whole semiotic charge that has its origins in the problematic ideologies that founded modernity.

The house is built like a stilt, 1.5 m from the ground. This constructive form is essentially a functional response and was created to respond to the problem of flooding; in the case of Farnsworth House, to protect the house from the floods of the river. But this paving stone becomes a sign of the symbolic type. In addition to having the characteristics of the aesthetic sign, as a work of art by the architect Mies Van Der Rohe, the house was arbitrarily assigned the function of representing the modernist movement.

The house floats on thin pillars. It rises, transcends matter. The work no longer touches the earth, it floats above it. The human being no longer looks up to contemplate nature. Now he watches it as an equal. The elevation of the house not only serves to protect from the uncontrollable violence of the environment, but also to place the geometric shape invented by humanity on the same level as those created by nature.

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

Mies appears in the story as a man "of great charm and charisma", while Edith "was painfully lonely, bored and overwhelmed" (Friedman, 1998: 131). According to biographers and essayists of that time, Edith's denunciation had nothing to do with the quality of the project, it was a reaction motivated by resentment arising from her amorous frustration. It was this version that became popular with the publication and dissemination of Mies Van Der Rohe - A Critical Biography - Franz Schulze. He quotes Van der Rohe himself, though he never investigated the circumstances or the accuracy of the account: “The old maid that would have wanted ‘the architect to come with the house’" (Schulze, Mies van der Rohe, 253).

Farnsworth House is a United States National Historic Landmark as a masterpiece of modern architecture. It transposes immateriality, made for immaterial residents. Its furniture is well ordered and designed - this is the text we read when we open the house's official website, an expression of the genius of a man who has the ability to materialize a spectral structure for immaterial inhabitants.

***

Umberto Eco, in his book “The Absent Structure,” reflects on the impossibility of understanding architecture or design objects based only on their functionality. And to carry out a more complete and complex analysis of these productions, such as that undertaken by semiotics, we must look at them not only as functional signs, but as more complex phenomenological and cultural manifestations.

If we understand that the architecture of Farnsworth House is as much made up of steel, glass and cement, as it is of the myths that propelled it into existence, we can say that it is the first “domestic glass box” in history, with all that that can mean in terms of a rationalist model of existence. Its materials and design carry a whole semiotic charge that has its origins in the problematic ideologies that founded modernity.

The house is built like a stilt, 1.5 m from the ground. This constructive form is essentially a functional response and was created to respond to the problem of flooding; in the case of Farnsworth House, to protect the house from the floods of the river. But this paving stone becomes a sign of the symbolic type. In addition to having the characteristics of the aesthetic sign, as a work of art by the architect Mies Van Der Rohe, the house was arbitrarily assigned the function of representing the modernist movement.

The house floats on thin pillars. It rises, transcends matter. The work no longer touches the earth, it floats above it. The human being no longer looks up to contemplate nature. Now he watches it as an equal. The elevation of the house not only serves to protect from the uncontrollable violence of the environment, but also to place the geometric shape invented by humanity on the same level as those created by nature.

Do I feel implacable calm?…The truth is that in this house with its four walls of glass I feel like a prowling animal, always on the alert. I am always restless. Even in the evening. I feel like a sentinel on guard day and night. I can rarely stretch out and relax…

What else? I don’t keep a garbage can under my sink. Do you know why? Because you can see the whole ‘kitchen’ from the road on the way in here and the can would spoil the appearance of the whole house. So I hide it in the closet farther down from the sink. Mies talks about his ‘free space’: but his space is very fixed. I can’t even put a clothes hanger in my house without considering how it affects everything from the outside. Any arrangement of furniture becomes a major problem, because the house is transparent, like an X-ray. 8

What else? I don’t keep a garbage can under my sink. Do you know why? Because you can see the whole ‘kitchen’ from the road on the way in here and the can would spoil the appearance of the whole house. So I hide it in the closet farther down from the sink. Mies talks about his ‘free space’: but his space is very fixed. I can’t even put a clothes hanger in my house without considering how it affects everything from the outside. Any arrangement of furniture becomes a major problem, because the house is transparent, like an X-ray. 8

8

Joseph A. Barry “Report on the American Battle between Good and Bad Modern houses” House Beautiful 95, May 1953 – 270. In WENDL.

For Edith, the stilt house ends up recreating meanings that are completely removed from the semantic axis of the house: of a cage when inside, of a display window when outside. However, despite the anger directed at Mies for his arrogance and the cost of the project, the house eventually became her weekend spot, her original wish. Edith used it for this purpose for 20 years and, during this period, she wrote some letters revealing her relationship with the house. If in the first years she wrote of discomfort in her diary, over time she reveals the small pleasures and encounters with her home. In her diary, she recounts her first days in the house, and the many inadvertent invaders whose purpose it was to observe her more closely. In an excerpt from her diary, Farnsworth tells of sharing dinner with a stranger—an eminent Scottish art professor who came to see the house—wherein they discussed literature and the horrors of war. She becomes aware of the satisfying potential that the house has, not only to bring natural and spiritual beauty into its walls, but to provide moments of pleasant connection like this:

Mr. Michael Jaffe came late one afternoon and I liked him well enough to share a chicken with him for supper. By that time I had a proper woodpile and the firelight brought out the shadows of swelling buds on the black maple at this end of the terrace. We talked about [British author] Cyril Connolly and his ―Unquiet Grave‖ and the collapse of the review Horizon. ―Do you remember the terrible story of the oil slick—in the Baltic, wasn‘t it, that trapped the seagulls so that they couldn‘t get off the surface, and the boys who stoned them from shore? I think that was in the last issue of Horizon.

(...) As of that evening, passed in the company of a stranger who shared not only the chicken, but Connolly in his pervading angst and his fascinating anecdote and the swelling buds and the stoned and dying birds—the glass house took on life and became my own home. 9

(...) As of that evening, passed in the company of a stranger who shared not only the chicken, but Connolly in his pervading angst and his fascinating anecdote and the swelling buds and the stoned and dying birds—the glass house took on life and became my own home. 9

9 Farnsworth, Edith. Memórias 12-13. In WENDL. Tradução livre pela autora do artigo.

Farnsworth maintained a lifelong commitment to producing art. This occurred intensively as a resident of the house from 1951 to 1971. During this period, she wrote poems and took photographs translating her relationship with the glass space. Her photographs contrast with the official photos. From the house, wild plants and a dense forest emerge. The transparency was rendered opaque by the aluminum screens Edith had installed on the porch to protect herself from the swarm of mosquitoes that emerged from the river just a hundred feet away. Wild foliage and vines twined around the steel beams, and cobwebs tangled in the apparent structures. The glass windows in the photos alternate between transparency and mirror, prism and shadow play, with sunlight streaming through the leaves and branches. These photographs illustrate Edith's perceptions of the violent domestication of nature:

“… something has happened to nature…she has become secularized, even domesticated. Today, she rubs her muzzle on the windowpane.”

10

![]()

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

10

Edith B. Farnsworth. “The Poets and the Leopard”. Northwestern TriQuartely (Autumn, 1960), 6 – 12, This quote is from page 6.

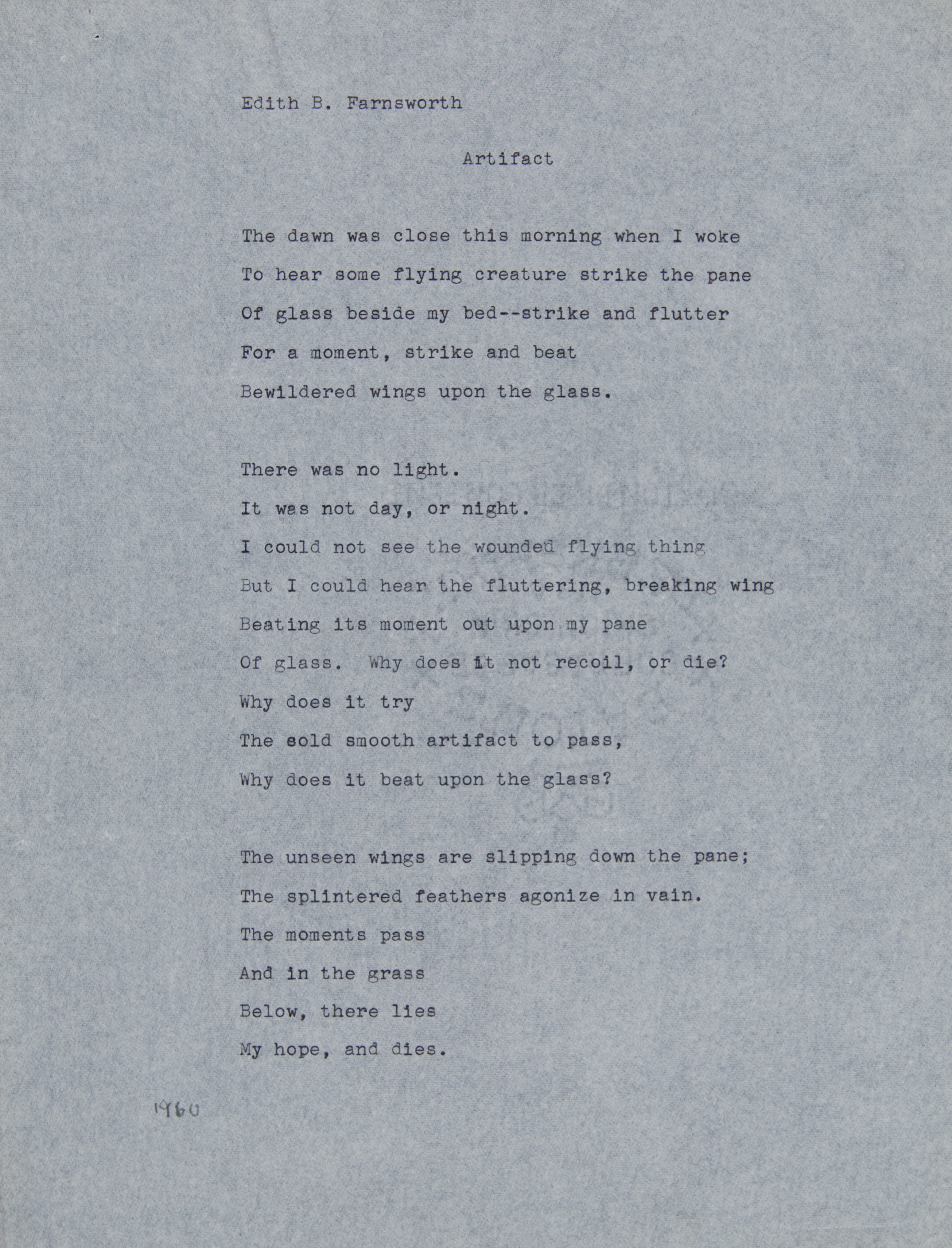

Farnsworth's poems contribute to a perception of beauty from living with the environment. The glass house appears in the works not as a scenario or neutral object, it is the “subject” that provides experiences and contemplations, that activates events. The poems evaluate the transitory events that the house provides

11 FARNSWORTH, Edith. “Artefact”. Memoirs. Chicago: Newberry Library Archives. – box no. 2, folder 34.

Xenia 1.

Dear little insect

Known to everyone as “fly”, I don’t know why,

This evening almost at dark,

As I was reading Deuteroisaiah

You reappeared beside me,

But you didn’t have your glasses,

You couldn’t see me;

Nor could I, without that little glint,

Recognize you in the gloom.

Artifact.

The dawn was close this morning when I woke

To hear some flying creatures strike the pane

Of glass beside my bed – strike and flutter

For a moment, strike and beat

Bewildered wings upon the glass.

There was no light.

It was not day, or night.

I could not see the wounded flying thing

But I could hear the fluttering, breaking wing

Beating its moment out upon my pane

Of glass. Why does it not recoil, or die?

The unseen wings are slipping down the pane;

The splintered feathers agonize in vain.

The moments pass

And in the grass

Below, there lies

My hope, and dies

Dear little insect

Known to everyone as “fly”, I don’t know why,

This evening almost at dark,

As I was reading Deuteroisaiah

You reappeared beside me,

But you didn’t have your glasses,

You couldn’t see me;

Nor could I, without that little glint,

Recognize you in the gloom.

Artifact.

The dawn was close this morning when I woke

To hear some flying creatures strike the pane

Of glass beside my bed – strike and flutter

For a moment, strike and beat

Bewildered wings upon the glass.

There was no light.

It was not day, or night.

I could not see the wounded flying thing

But I could hear the fluttering, breaking wing

Beating its moment out upon my pane

Of glass. Why does it not recoil, or die?

The unseen wings are slipping down the pane;

The splintered feathers agonize in vain.

The moments pass

And in the grass

Below, there lies

My hope, and dies

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

A bird crashes into her window in the poem “Artifact”. The house appears as something that provokes experiences. A bird lying in the grass, its wings broken, dead. Interaction with the home gives the animal's impact a sense of loss. The contradiction of the modernist house – a work to be contemplated versus a house to be experienced.

In the course of this work, we shall see that the imagination functions in this direc¬ tion whenever the human being has found the slightest shelter: we shall see the imagination build “walls” of im¬ palpable shadows, comfort itself with the illusion of pro¬ tection—or, just the contrary, tremble behind thick walls, mistrust the staunchest ramparts. In short, in the most interminable of dialectics, the sheltered being gives per¬ ceptible limits to his shelter. He experiences the house in its reality and in its virtuality, by means of thought and dreams.

12

12 BACHELARD, pag. 200

After its sale in 1972 to Peter Palumbo, the house underwent a major restoration. The new owner hired the company of Mies van der Rohe's grandson Dirk Lohan for the restoration, following his grandfather's original design. The furniture proposed by Mies was placed, and all the “paraphernalia” of Edith's life was eliminated, making the house return to 1951. An abstraction. The project was never intended to be inhabited. Life would spoil its transcendence. Its “immateriality” and “spirituality” were not in the proposal of a simple dwelling, dedicated to the contemplation of nature, but returned to its condition of historical work of art, museological object: a modernist house from the 1950s. A life-sized model of a representation of architecture of the international style. Upon returning to its initial condition as a model, an ideal aesthetic paradigm, it gained a mythical meaning. The story lived in it by Edith had to be erased. The past was hijacked, masked and forgotten. Myth took over reality.

As Umberto Eco proposes, we can think of culture as a system of signs, and this means that, in the universe of culture, objects, images and even people are causes and agents of discourse. These discourses are historically constructed by historical subjects of a space and a time. They talk to someone who wants to listen. The discourses made about the Farnsworth house and its main characters, contractor and contracted, are due to a small group of people, originally; these discourses that have lasted until today, at least on the official website of the Farnsworth house.

In the exercise of questioning such discourses, we have two questions that are intertwined. One of them concerns the contradiction between the essential function of the work as a house - home - and the poetic function of the modernist work - museum object. And the other follows a path of inquiry in relation to the resources used to sustain and support the discourse. In this second question, in the case of the Farnsworth house, it meant erasing the history of the work’s trajectory as an inhabited house, staining the image of the woman who commissioned it. The conflict between the architect's project, which should be preserved in its original and creative conception, and the owner of the house, who made it her home. Even with all the difficulties anticipated and experienced in the natural space where the house was built, the discourse was metamorphosed into a question of superiority of the “man” creator and the “woman” that corrupts the original project.

As Umberto Eco proposes, we can think of culture as a system of signs, and this means that, in the universe of culture, objects, images and even people are causes and agents of discourse. These discourses are historically constructed by historical subjects of a space and a time. They talk to someone who wants to listen. The discourses made about the Farnsworth house and its main characters, contractor and contracted, are due to a small group of people, originally; these discourses that have lasted until today, at least on the official website of the Farnsworth house.

In the exercise of questioning such discourses, we have two questions that are intertwined. One of them concerns the contradiction between the essential function of the work as a house - home - and the poetic function of the modernist work - museum object. And the other follows a path of inquiry in relation to the resources used to sustain and support the discourse. In this second question, in the case of the Farnsworth house, it meant erasing the history of the work’s trajectory as an inhabited house, staining the image of the woman who commissioned it. The conflict between the architect's project, which should be preserved in its original and creative conception, and the owner of the house, who made it her home. Even with all the difficulties anticipated and experienced in the natural space where the house was built, the discourse was metamorphosed into a question of superiority of the “man” creator and the “woman” that corrupts the original project.

© Edith Farnsworth Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

Referências bibliográficas

ECO, Umberto. A Estrutura Ausente. São Paulo: Editora perspectiva,1971.

BACHELAR, Gaston. A Poética do Espaço. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1993.

CORBETT, Kathleen LaMoine. Tilting at Modern: Elizabeth Gordon's "The Threat to the Next America". Chapter one: the world and the woman behind “THE THREAT TO THE NEXT AMERICA”. 2010. Tese (Doutorado). Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley, p. 1 – 31 e p.133 – 155.

SCHULZE, F. e WINDHORST, Edward. Mies van der Rohe; A Critical Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1985.

BACHELAR, Gaston. A Poética do Espaço. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1993.

CORBETT, Kathleen LaMoine. Tilting at Modern: Elizabeth Gordon's "The Threat to the Next America". Chapter one: the world and the woman behind “THE THREAT TO THE NEXT AMERICA”. 2010. Tese (Doutorado). Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley, p. 1 – 31 e p.133 – 155.

SCHULZE, F. e WINDHORST, Edward. Mies van der Rohe; A Critical Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1985.

BARRY, JA (1953). Report on the Battle between Good and Bad Modern Houses. House Beautiful 95 (5): 172–73; 266–72.

FARNSWORTH, Edith. Memoirs. Chicago: Newberry Library Archives.

FRIEDMAN, AT. People who live in glass houses: Edith Farnsworth, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Philip Johnson. Women and the making of the modern house: a social and architectural history. New York: Abrams. 1998

GORDON, E. The Threat to the Next America. House Beautiful 97(4): 126-130; 250-251.1953

WENDL, Nora. Uncompromising Reasons for Going West: A Story of Sex and Real Estate, Reconsidered. Thresholds, Cambridge, Massachusetts, (43), pp. 20–361. 2015.

FARNSWORTH, Edith. Memoirs. Chicago: Newberry Library Archives.

FRIEDMAN, AT. People who live in glass houses: Edith Farnsworth, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Philip Johnson. Women and the making of the modern house: a social and architectural history. New York: Abrams. 1998

GORDON, E. The Threat to the Next America. House Beautiful 97(4): 126-130; 250-251.1953

WENDL, Nora. Uncompromising Reasons for Going West: A Story of Sex and Real Estate, Reconsidered. Thresholds, Cambridge, Massachusetts, (43), pp. 20–361. 2015.

PRECIADO, Paul B. Traduzido por HARRIS, Keith. Mi(e)s Conception: The Farnsworth House and the Mystery of the Transparent Closet. Feminist, Queer and Trans Geographies. Novembro, 2019. Available at: https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/mies-conception-the-farnsworth-house-and-the-mystery-of-the-transparent-closet.

FRACALOSSI, Igor. Clássicos da Arquitetura: Casa Farnsworth / Mies van der Rohe 27 Mar 2012. ArchDaily Brasil. Acessado 2 Ago 2020. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/01-40344/classicos-da-arquitetura-casa-farnsworth-mies-van-der-rohe

Edith Farnworth House Official Website

https://farnsworthhouse.org/history-farnsworth-house/

FRACALOSSI, Igor. Clássicos da Arquitetura: Casa Farnsworth / Mies van der Rohe 27 Mar 2012. ArchDaily Brasil. Acessado 2 Ago 2020. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/01-40344/classicos-da-arquitetura-casa-farnsworth-mies-van-der-rohe

Edith Farnworth House Official Website

https://farnsworthhouse.org/history-farnsworth-house/