A peripheral cosmogony: On the 6th São Paulo Art Biennial

Erica Ferrari

Periphery: a word that transports us to the complexity of the contemporary moment, so present in current thinking about the continuous transformation of power discourses - cities, the world, art.

“All modern art was inspired by the art of peripheral peoples [...]”

1

– with this clarity of perception, the critic Mário Pedrosa

2

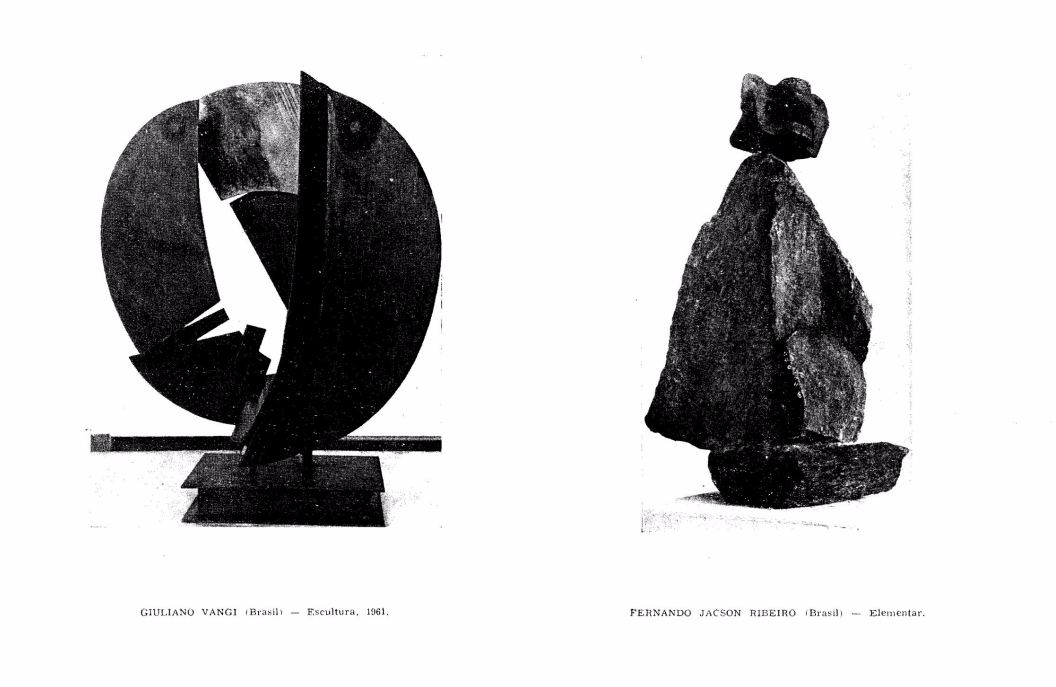

undertook some of the most radical proposals for the Brazilian institutional art circuit. Among them, the 6th São Paulo Art Biennial, organized by him in 1961, brought productions from different [supposed] “peripheries,” from different times, from the most diverse contexts – presenting a set of aesthetic, symbolic and social richness that still reverberates. What must it have been like to see, side by side, a set of medieval frescoes from the former Yugoslavia, the work of Kurt Schwitters and baroque sculptures from Paraguay? Or Clemente Orozco's painting, Australian Aboriginal pieces and the works of Pedro Figari? This conjunction of manifestations seems in fact capable of disturbing the parameters of what could be considered until then as modern art – understood as the highest creation of Western society.

1. Speech given at a meeting of the Standing Committee for the Reconstruction of MAM held at the School of Visual Arts in Lage Park, 1978.

2. Art critic, journalist and left-wing political activist. For an introduction to Mário's thought and trajectory, read ARANTES, Otília. ‘Mário Pedrosa - Itinerário Crítico’ São Paulo: Cosac&Naify, 2004.

Pedrosa's proposal for the 6th Biennial sought to remove the works of contemporary artists from the specialized isolation of modern art museums, then in vogue. By ending specialization, he contradicted the traditional historiography of art, which imposed on certain works and objects the label of “predecessors”: Aboriginal, Hindu, Baroque and the European 1800s, and Latin American art seem to ricochet in the photos of the construction of Brasília, in Alicia Penalba's bronzes, in Lygia Clark's critter.

A reflection on the (peripheral) origins of modern already vividly transpired as a guiding principle of Pedrosa’s thought – an idea that almost two decades later will fully reveal itself in his (not implemented) proposal for a Museum of Origins during the reconstruction of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro after the great fire of 1978

3

. Today, periphery is the word that transports us to the complexity of the contemporary moment, so present in the current thinking of continuous transformation of power discourses - of cities, of the world, of art.

![]()

3.

More about the Museum of Origins project in PARRACHO, Sabrina. ‘Mário Pedrosa e as musas: reflexões sobre crítica e projetos museais.’ In: ‘Mário Pedrosa Atual.’ Rio de Janeiro: Odeon Institute, 2019.

In the early 1960s, politically engaged, conceptual and pop strands of art emerged as the metropolitan face of culture, contesting language and anchored in experimentalism, the inflection of a capitalist consumer society. In a movement to revise the Biennial itself, but also to expand its parameters, the 6th edition of the event offered a cosmogony of its own. In the brief text of the catalog, Pedrosa discusses this movement as “universality” and associates this characteristic with the constitution of post-colonial nations in America:

“It has become [the Biennial], therefore, without favor, at the present time, the most universal artistic manifestation in the world. This universality is not only translated on the political plane, that is, in space; but it also translates in time [...]. This trait of universality is increasingly characteristic of the angle of vision of the young American world of which we are a part. From here, from our quadrant, we do not distinguish privileged historical and artistic periods [...]. All artistic expressions, past or present, whether from the West or the East, form part of our sensibility and our art.” 4

4.

Presentation text of the Catalog of the 6th São Paulo Art Biennial, 1961.

In an update to the concept of building a national or regional character, the spiral turns not in the sense of swallowing European culture, as the modernists of previous decades advocated, but in the sense of illuminating all autochthonous productions, which in the first instance, were a creative trigger for the modernist artistic avant-gardes. In this way, there is a subtle but all-important transformation in the qualification of non-modernist, non-Western art, which makes us understand an adherence to the suppression of the notion of historical evolution and of qualitative judgments proper to a supposedly universal and univocal notion of civilization.

This displacement was significant for an art biennial that was idealized as a reflection of the national modernist project, a desire for cultural internationalization, but also to valorize the local production from this internationalization. From its first edition in 1951 until the following decade, it would consist of a private initiative, centered on the figure of a preponderant sponsoring dealer. The 6th edition of 1961 brought the beginning of a break from the current model of the event so far, as much in the functional-bureaucratic aspect as in the curatorial relationship. With the change of businessman Ciccilo Matarazzo as the only patron, the Biennial faced economic difficulties for the first time. Sponsoring companies assumed the cost of rooms, printed material and pedagogical projects, while complementary activities became more relevant, such as stores and advertising booths. In the catalog, there are over one hundred pages with the ads and dedications of large firms that began to sustain the show: Esso, Lufthansa, Gessy Lever, Probel, Aerolineas Argentinas, Coral. Somehow, these pages lead us to the modern dream of a union between industry and art, between the technological production of a factory and human artistic production, so present in the proposals of concretist artists, for example. However, all these indications, from Pedrosa's performance to the loss of Matarazzo's financial hegemony and the outsourced business presence, denote a profound crisis of modernism and the beginning of the crumbling of its operational mode. Decentralization—of hegemonic discourses, of the capital of the great entrepreneur, of the European cultural domain—began its journey, so culturally present today.

This displacement was significant for an art biennial that was idealized as a reflection of the national modernist project, a desire for cultural internationalization, but also to valorize the local production from this internationalization. From its first edition in 1951 until the following decade, it would consist of a private initiative, centered on the figure of a preponderant sponsoring dealer. The 6th edition of 1961 brought the beginning of a break from the current model of the event so far, as much in the functional-bureaucratic aspect as in the curatorial relationship. With the change of businessman Ciccilo Matarazzo as the only patron, the Biennial faced economic difficulties for the first time. Sponsoring companies assumed the cost of rooms, printed material and pedagogical projects, while complementary activities became more relevant, such as stores and advertising booths. In the catalog, there are over one hundred pages with the ads and dedications of large firms that began to sustain the show: Esso, Lufthansa, Gessy Lever, Probel, Aerolineas Argentinas, Coral. Somehow, these pages lead us to the modern dream of a union between industry and art, between the technological production of a factory and human artistic production, so present in the proposals of concretist artists, for example. However, all these indications, from Pedrosa's performance to the loss of Matarazzo's financial hegemony and the outsourced business presence, denote a profound crisis of modernism and the beginning of the crumbling of its operational mode. Decentralization—of hegemonic discourses, of the capital of the great entrepreneur, of the European cultural domain—began its journey, so culturally present today.

Neo-concretist works were highlighted at the show, with Lygia Clark winning the grand prize for sculpture. “This award represents a break with the traditional canons of modern art. It brings international appreciation to the revolutionary intervention of the ‘Critters,’ a construction of planes articulated in space by hinges and that are armed and combined through the spectator’s actions. He begins to participate, so to speak, in the work. The spectator does not leave everyday life contemplating; he leaves acting, making.” The emphasis on Lygia’s work seems to close the cycle proposed for this edition of the Biennial: subverting the genealogy of modern art and presenting an overview of artistic creation as a broad and timeless field, with the relationship between making and fruition as the principle of activity. The “other,” the periphery, the original, are revealed in the special rooms dedicated to the production of Nigeria and the Ivory Coast, in the first African participation in the event, or in the massive exhibition of Latin American works, from countries such as Colombia and Chile. Ciccillo Matarazzo, in the preface to the catalogue, emphasizes the unprecedented participation of other non-Western nations, such as the USSR, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, in addition to the large room dedicated to Sino-Japanese calligraphy, an object of study for Mário Pedrosa. But the other, the periphery, the original, are also revealed in contemporary Brazilian production, in the openness and maturity of the neo-concrete artists, where the need to decolonize becomes urgent and essential. A still relevant need, whose aesthetic and political manifestations took other contours in the face of contemporary challenges.

![]()

PEDROSA, Mario. “‘A Bienal de Cá para Lá”’, in‘ Mundo, homem, arte em crise’. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 1975.